Warning: This text discusses main spoilers for “Wolf Man.”

Earlier than Leigh Whannell took his abilities to the Common Monsters franchise for a double dip, the Australian filmmaker first plied his commerce as an actor, a author on the “Noticed” and “Insidious” franchises, and (most significantly for our functions right here) a director who first made a reputation for himself with trendy, low-budget thrillers. His exact profession trajectory has hardly been a typical one in comparison with most, however the broad strokes of working his manner up the studio system till reaching his apex — so far, no less than — with “The Invisible Man” and most lately “Wolf Man” (which I reviewed for /Film here) could not have been extra superb. It is onerous to overlook how his newest monster film appears like a fruits of virtually each lesson discovered in “The Invisible Man,” significantly with its strategy to creating the title character really feel contemporary and trendy. However greater than the rest, “Wolf Man” echoes again to arguably Whannell’s most underrated film of all: “Improve.”

The 2018 sci-fi flick immediately made waves upon launch (you possibly can check out /Film’s glowing review by Matt Donato here) and impressed one thing of a cult following for its ingenious camerawork, its genre-bending story, and the truth that it did Venom higher than any of the particular “Venom” films ever did. The movie follows Logan Marshall-Inexperienced as Gray Hint, an old-school junker/mechanic who finally ends up implanted with a cutting-edge chip (and its accompanying synthetic intelligence, STEM) that primarily turns him right into a high-tech vigilante.

On the floor, neither “Wolf Man” nor “Improve” would appear to share a lot in widespread … till you’re taking a deeper take a look at how each deal with the thought of perspective, autonomy, and the way in which we depict these ideas in movie.

The most effective a part of Wolf Man is extra than simply fancy filmmaking

It sounds dumb to say (sort?) it out loud like this, however the whole lot we see depicted in a film or tv present was performed with appreciable quantities of intentionality and function. Consider any closeup/insert shot of a hand holding a espresso mug or cellphone display, an establishing shot displaying us the skyline of a metropolis or the outside of a constructing, or the huge array of colours that make up the manufacturing design, costumes, and total look of a complete film. All of it was performed for a particular motive — whether or not to evoke a selected emotion, talk some key bit of knowledge, or just present context for the remainder of the scene.

So on the subject of what’s nearly sure to be the most important and finest speaking level in “Wolf Man” (aside from all that controversy over the creature design), it is price digging deeper into why Leigh Whannell determined to shoot these gnarly-looking scenes from the Wolf Man’s perspective the way in which that he and director of pictures Stefan Duscio did.

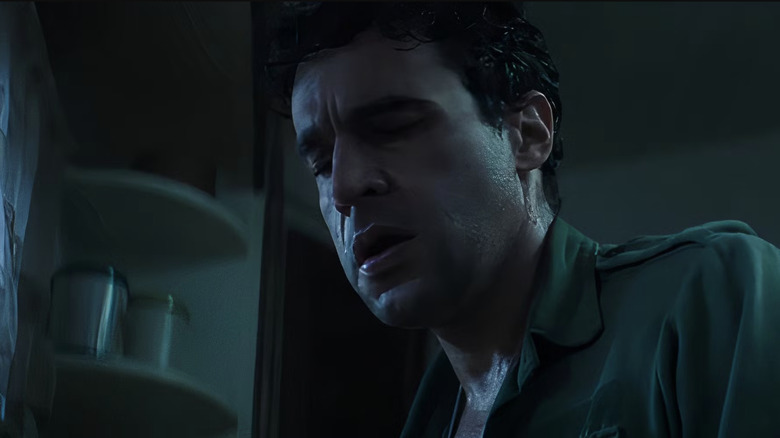

The primary of those trippy moments comes after poor Blake (Christopher Abbott) has already been scratched by the Wolf Man throughout that tense automobile crash within the Oregon forest early on, and is now progressively succumbing to his signs. At first, we do not get a full image of what is improper. Positive, he appears just a little sweaty and nervous, however in any other case appears succesful sufficient of defending his household. That’s, till he is noisily boarding up the entrance door of the cabin, his spouse Charlotte (Julia Garner) and daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth) wander into the hallway, and simply … stare at him blankly. It is not till just a few scenes later that we uncover that they’re not those performing bizarre — he’s. After locking audiences strictly within the standpoint of Blake, the digicam easily pans over to Charlotte’s perspective and divulges the complete extent of her husband’s transformation into the Wolf Man. The lighting dramatically modifications, the very framing of the digicam actually tilts off its axis, and we understand that Blake’s situation has already worsened considerably. He cannot communicate, his wounds have festered, and he is properly on his strategy to turning into the Wolf Man.

How Wolf Man and Improve pull of comparable tips

In each “Improve” and “Wolf Man,” Leigh Whannell’s intelligent filmmaking selections are utilizing the conventions and our personal expectations of the style to maintain viewers on their toes. “Improve” principally depends on wildly jarring tilts and pictures that ignore the same old horizons of a body — all of which disorients us and assist us purchase into the hard-hitting motion. (The second Gray permits the AI in his head to completely take over his physique and combat his battles for him, as seen in this clip, is the earliest and handiest instance of this within the film.) Though “Wolf Man” by no means opts for this maximized strategy of managed chaos, Whannell’s comparable option to utterly alter the visible language of the movie accomplishes a lot the identical impact.

In “Wolf Man,” Whannell and director of pictures Stefan Duscio reunite — sure, additionally they labored collectively on each “The Invisible Man” and “Improve,” which ought to hardly come as a shock — and work their distinctive magic over again. On this case, they depend on a way more subdued methodology to place audiences again on their heels. After placing us completely within the headspace of Blake for your complete film, the place we hardly ever (if ever) see something that he would not see himself, we immediately change locations because the digicam fairly actually glides over to Charlotte’s perspective. This primary happens at Blake’s bedside, and once more within the darkened basement as she frantically requires assistance on the CB radio … although we initially see this within the night time imaginative and prescient and with the muddled audio that Blake experiences in his sensory-overloaded state.

Whereas it is a utterly completely different shift in perspective than what the duo pulls off in “Improve,” Whannell and Duscio discover an equally as efficient strategy to hold us unsettled throughout these moments in “Wolf Man,” all whereas staying 100% devoted to the wildly completely different tones of every respective film. The Leigh Whannell who made “Wolf Man” merely could not have performed it with out the Leigh Whannell who first wowed us with “Improve” — and we’re fortunate to have each.

“Wolf Man” is now taking part in in theaters.

Warning: This text discusses main spoilers for “Wolf Man.”

Earlier than Leigh Whannell took his abilities to the Common Monsters franchise for a double dip, the Australian filmmaker first plied his commerce as an actor, a author on the “Noticed” and “Insidious” franchises, and (most significantly for our functions right here) a director who first made a reputation for himself with trendy, low-budget thrillers. His exact profession trajectory has hardly been a typical one in comparison with most, however the broad strokes of working his manner up the studio system till reaching his apex — so far, no less than — with “The Invisible Man” and most lately “Wolf Man” (which I reviewed for /Film here) could not have been extra superb. It is onerous to overlook how his newest monster film appears like a fruits of virtually each lesson discovered in “The Invisible Man,” significantly with its strategy to creating the title character really feel contemporary and trendy. However greater than the rest, “Wolf Man” echoes again to arguably Whannell’s most underrated film of all: “Improve.”

The 2018 sci-fi flick immediately made waves upon launch (you possibly can check out /Film’s glowing review by Matt Donato here) and impressed one thing of a cult following for its ingenious camerawork, its genre-bending story, and the truth that it did Venom higher than any of the particular “Venom” films ever did. The movie follows Logan Marshall-Inexperienced as Gray Hint, an old-school junker/mechanic who finally ends up implanted with a cutting-edge chip (and its accompanying synthetic intelligence, STEM) that primarily turns him right into a high-tech vigilante.

On the floor, neither “Wolf Man” nor “Improve” would appear to share a lot in widespread … till you’re taking a deeper take a look at how each deal with the thought of perspective, autonomy, and the way in which we depict these ideas in movie.

The most effective a part of Wolf Man is extra than simply fancy filmmaking

It sounds dumb to say (sort?) it out loud like this, however the whole lot we see depicted in a film or tv present was performed with appreciable quantities of intentionality and function. Consider any closeup/insert shot of a hand holding a espresso mug or cellphone display, an establishing shot displaying us the skyline of a metropolis or the outside of a constructing, or the huge array of colours that make up the manufacturing design, costumes, and total look of a complete film. All of it was performed for a particular motive — whether or not to evoke a selected emotion, talk some key bit of knowledge, or just present context for the remainder of the scene.

So on the subject of what’s nearly sure to be the most important and finest speaking level in “Wolf Man” (aside from all that controversy over the creature design), it is price digging deeper into why Leigh Whannell determined to shoot these gnarly-looking scenes from the Wolf Man’s perspective the way in which that he and director of pictures Stefan Duscio did.

The primary of those trippy moments comes after poor Blake (Christopher Abbott) has already been scratched by the Wolf Man throughout that tense automobile crash within the Oregon forest early on, and is now progressively succumbing to his signs. At first, we do not get a full image of what is improper. Positive, he appears just a little sweaty and nervous, however in any other case appears succesful sufficient of defending his household. That’s, till he is noisily boarding up the entrance door of the cabin, his spouse Charlotte (Julia Garner) and daughter Ginger (Matilda Firth) wander into the hallway, and simply … stare at him blankly. It is not till just a few scenes later that we uncover that they’re not those performing bizarre — he’s. After locking audiences strictly within the standpoint of Blake, the digicam easily pans over to Charlotte’s perspective and divulges the complete extent of her husband’s transformation into the Wolf Man. The lighting dramatically modifications, the very framing of the digicam actually tilts off its axis, and we understand that Blake’s situation has already worsened considerably. He cannot communicate, his wounds have festered, and he is properly on his strategy to turning into the Wolf Man.

How Wolf Man and Improve pull of comparable tips

In each “Improve” and “Wolf Man,” Leigh Whannell’s intelligent filmmaking selections are utilizing the conventions and our personal expectations of the style to maintain viewers on their toes. “Improve” principally depends on wildly jarring tilts and pictures that ignore the same old horizons of a body — all of which disorients us and assist us purchase into the hard-hitting motion. (The second Gray permits the AI in his head to completely take over his physique and combat his battles for him, as seen in this clip, is the earliest and handiest instance of this within the film.) Though “Wolf Man” by no means opts for this maximized strategy of managed chaos, Whannell’s comparable option to utterly alter the visible language of the movie accomplishes a lot the identical impact.

In “Wolf Man,” Whannell and director of pictures Stefan Duscio reunite — sure, additionally they labored collectively on each “The Invisible Man” and “Improve,” which ought to hardly come as a shock — and work their distinctive magic over again. On this case, they depend on a way more subdued methodology to place audiences again on their heels. After placing us completely within the headspace of Blake for your complete film, the place we hardly ever (if ever) see something that he would not see himself, we immediately change locations because the digicam fairly actually glides over to Charlotte’s perspective. This primary happens at Blake’s bedside, and once more within the darkened basement as she frantically requires assistance on the CB radio … although we initially see this within the night time imaginative and prescient and with the muddled audio that Blake experiences in his sensory-overloaded state.

Whereas it is a utterly completely different shift in perspective than what the duo pulls off in “Improve,” Whannell and Duscio discover an equally as efficient strategy to hold us unsettled throughout these moments in “Wolf Man,” all whereas staying 100% devoted to the wildly completely different tones of every respective film. The Leigh Whannell who made “Wolf Man” merely could not have performed it with out the Leigh Whannell who first wowed us with “Improve” — and we’re fortunate to have each.

“Wolf Man” is now taking part in in theaters.